You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

There has hardly been an easier target for disdain in higher education circles than the federal graduation rate produced through the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. The federal government's primary data collection vehicle for higher education is both essential and subpar, particularly when it comes to measuring how students move into and through the postsecondary ecosystem.

The graduation rate, whose importance as an accountability measure for institutions has spiked along with the U.S. government's spending on student financial aid, has been rightly derided as flawed because it has included only those students who enroll full-time and are entering college for the first time (leaving out the ever-increasing numbers of part-time students and those who switch colleges or return as adults). At many community colleges and other institutions that serve large numbers of older students, particularly, the graduation rate has ranged from misleading to virtually useless. ("Flawed" is one of the kinder things you'll hear it called.)

Today, the Education Department's National Center for Education Statistics unwraps a revision of the IPEDS database that will expand the government's tools for measuring postsecondary outcomes, especially for the students who, for lack of a better term, are frequently called "nontraditional" (even though they now outnumber the "traditional" 18- to 22-year-olds).

While the changes are partial and leave many policy makers wanting more -- most of which cannot be accomplished unless and until the federal government ends its ban on collecting student-level data -- they are widely seen as a vast improvement.

"This is a step in the right direction, and it's a big step forward for community colleges, particularly," said Andrew Nichols, director of higher education research and data analytics at the Education Trust, which advocates for low-income and minority students.

Among the most significant changes: for the first time, the government is publishing completion data for part-time and non-first-time students at every two- and four-year degree- or certificate-granting institution, providing a new tool (beyond the existing graduation rate) for gauging institutions' performance. In addition, IPEDS will supplement the existing graduation rate data by providing information on Pell Grant recipients at every college or university that awards federal financial aid.

And in perhaps the most interesting finding from this first (preliminary) release of data, students who were enrolled full-time (but were not first-time enrollees in college) and were seeking a degree or certificate were likelier to earn a credential within eight years than were full-time, first-time students at public four-year, public two-year and for-profit institutions. In other words, transfer students appeared to outperform their peers who started at their colleges right out of high school.

Decade in the Making

The just-released government data have their roots in legislation from nearly 10 years ago. The 2008 bill that extended the Higher Education Act of 1965 created a panel called the Committee on Measures of Student Success, which was charged with advising the Education Department specifically on how to improve the measures of success for two-year institutions. Community college leaders had long complained that by counting only full-time, first-time students, the federal graduation rate ignored many if not most of their students, and that by gauging success only by the awarding of a degree or credential, the government shortchanged a significant part of their mission -- preparing students for transfer.

The panel's recommendations set in motion a years-long process in which federal officials worked with researchers and higher ed leaders to refine a set of measures to capture more fully the extent to which students with different backgrounds and traits navigate higher education.

The result can be seen both in changes to the graduation rate and, most significantly, in the brand-new Outcome Measures section.

Beginning today, the downloadable IPEDS data for every degree- and certificate-granting college or university will include the six-year graduation rate for recipients of Pell Grants and subsidized Stafford Loans as well as for other types of students. This is designed to give policy makers a better sense of how colleges are faring with students whose educations the federal government is helping to subsidize.

"Adding Pell students to this was critically important to understanding the outcomes for economically disadvantaged students," said Richard Reeves, chief of the postsecondary branch at the National Center for Education Statistics.

The broader changes, however, are in the new Outcome Measures section, the data for which are available for every degree- and certificate-granting institution.

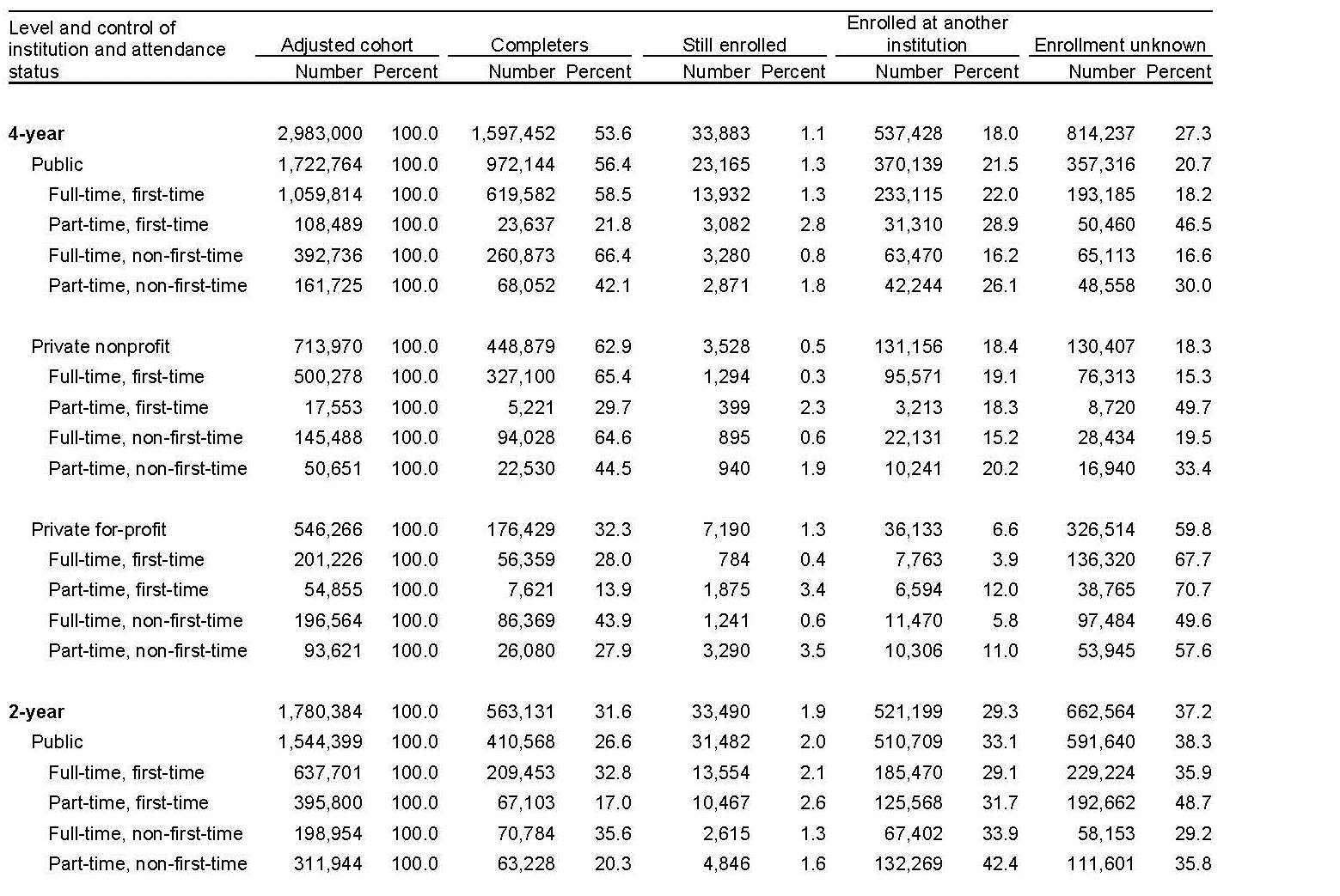

Each public, private and for-profit two-year and four-year institution is now reporting data about all students who entered a degree or certificate program, whether or not they are enrolled full-time or are first-time students. For each of those cohorts -- full-time first time, part-time first time, full-time non-first time, and part-time non-first time -- institutions report after eight years the number and proportion of students who (a) completed the credential, (b) were still enrolled, (c) had enrolled at another institution or (d) had unknown whereabouts.

The national data that emerge from those institutional reports are interesting. First, many more students are captured by the expanded analysis; public four-year institutions report 1,059,814 full-time, first-time students in the 2008 cohort, and 1,722,764 students over all. "This gives us a lens to look at about 650,000 additional people at those institutions alone," said Reeves.

Second, as seen in the table below, at most types of institutions, students who are enrolled full-time but are not enrolled in college for the first time are likelier to earn a credential within eight years than are their peers. That's true for two-year and four-year public institutions and two-year and four-year private for-profit colleges, but not for private nonprofit institutions. For instance, while 56.4 percent of full-time, first-time credential-seeking students at four-year public institutions earned a credential from that institution within eight years, 66.4 percent of non-first-time, full-time students did.

That might be because the returning students had transferred significant numbers of credits from their previous institutions or were more experienced at navigating through higher ed than their peers who started fresh. But this is likely to be a finding -- assuming the data are accurate, since these initial reports haven't been fully scrubbed by NCES -- that researchers are going to want to dig into.

What Hasn't Changed, and Can't (Without New Laws)

The IPEDS changes have been a long time coming, and experts on higher education data generally praised them. "We applaud the Education Department for doing what they can," said Elise Miller, vice president for research and policy at the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities (and a former expert on IPEDS at the Education Department).

Implicit in Miller's response -- echoed in the reactions of numerous analysts interviewed Wednesday -- is the reality that the department has done as much as it can given the constraints it is operating under.

While praising these changes, all of them cited various limitations of the data. Nichols, of Education Trust, for instance, noted that the outcome measures gauge whether students completed the credential they were specifically seeking (in other words, for example, whether students who came in seeking a bachelor's degree settled for a certificate).

Miller, of APLU, pointed out that unlike the Student Achievement Measure (SAM) -- a collaborative student-tracking effort among higher education associations and the National Student Clearinghouse -- even the updated IPEDS does not offer any insights into what happens to students who transfer across institutional and state lines. And also unlike the SAM effort, how institutions track students isn't done in a consistent way. "Progress but not perfection" is how she described the IPEDS improvements.

What would produce something closer to perfection? "You can't get there from an outcome measure survey," she said. Colleges and universities "can't report what they don't know," and the only way they could really know where students go after they leave the institution is through some kind of national student-level data system -- which Congress years ago barred the federal government from creating, citing privacy and other concerns.

"They're doing what they can within the current statute," Miller said. "But if we really want to report on student outcomes, we need to change the statute."